The Eleventh Hour

The Program

From 1961 until 1966, two medical dramas battled it out in prime time: Dr. Kildare on NBC and Ben Casey on ABC. Each starred a handsome, young title character (Richard Chamberlain as Kildare, Vince Edwards as Casey) with an older, more experienced mentor (Raymond Massey as Kildare’s Dr. Leonard Gillespie, Sam Jaffe as Casey’s Dr. David Zorba). Each series also spawned a spinoff focused on psychological matters: for Casey it was Breaking Point (1963–1964); for Kildare, The Eleventh Hour (1962–1964).

During the first season of The Eleventh Hour, Wendell Corey starred as veteran psychiatrist Dr. Theodore Bassett, with Jack Ging as his younger colleague, clinical psychologist Dr. Paul Graham. The storylines focused on Bassett’s role as a consultant to the Department of Corrections, for which he often testified in criminal cases. For the show’s second season, the producers replaced Corey, citing mundane explanations at the time, but later revealing that Corey’s alcoholism had prevented the actor from delivering his lines. Ralph Bellamy came on board as Dr. L. Richard Starke to replace Bassett and the second season of The Eleventh Hour shifted its emphasis to Starke and Graham’s private practice.

The Music

Jerry Goldsmith had composed the series theme and pilot score for Dr. Kildare as well as four subsequent episodes of the medical drama early during its first season, but his busy schedule precluded further involvement in the series. A number of composers contributed music to Kildare after Goldsmith, but Harry Sukman assumed the bulk of the scoring duties for the show’s first four seasons. When Kildare producers spun off The Eleventh Hour, they turned to Sukman to score that program as well, asking him to provide a theme. For the February 13, 1963, Eleventh Hour episode “Like a Diamond in the Sky,” guest star Julie London, who played a troubled torch singer, recorded a vocal version of that theme, with lyrics by producer Sam Rolfe and associate producer Irving Elman.

Although Sukman largely handled the scoring responsibilities for The Eleventh Hour, his heavy workload providing music for both that series and Dr. Kildare necessitated assistance from time to time. As Variety reported on September 5, 1963:

Williams and Stevens Tuning 11th Hour Segs

Johnny Williams and Mort Stevens have been signed by MGM-TV to score two episodes of The Eleventh Hour, which goes into its second season on NBC Oct. 2. Williams will tune “The Bronze Locust,” Stevens scoring “Cold Hands, Warm Heart.” Ralph Bellamy and Jack Ging star in series, produced by Norman Felton and Irving Elman.

As the 1963–1964 TV season debuted, John Williams (then billed as “Johnny”) was beginning his sixth year under contract to Revue, the television production arm of Universal Studios. In spite of this busy schedule, around Labor Day 1963 Williams found time to compose and orchestrate a score for “The Bronze Locust” (which would be the sixth episode of The Eleventh Hour broadcast during its second and final season), conducting the recording session on September 6, 1963.

“The Bronze Locust”

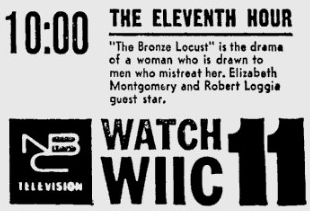

In this episode, first broadcast November 6, 1963, Elizabeth Montgomery and Robert Loggia guest-star as two patients of Dr. Starke who meet and begin a relationship fraught with danger. Montgomery plays Polly, an unstable young woman who initiates relationships with men likely to become abusive. “Polly Saunders subconsciously begins to evolve a plan that may result in her own death,” TV Guide wrote in its synopsis of the episode. “Twice wed to men who have treated her brutally, she is now drawn to David Marne.” Williams’ score features a melancholy theme for Polly, appearing as piano source music (“Polly's Theme”) and anchoring the dramatic score.

“I’ve Got You Under My Skin” (Porter)

The episode opens with an instrumental of Cole Porter’s “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” playing on the car radio of Polly Saunders (Elizabeth Montgomery), who sings along as she drives her convertible recklessly through city streets, blowing through stop signs.

Robert Baby

A police car, sirens blazing, follows Polly home, where she calmly opens the garage door. When the investigating officer (Bill Hickman) recognizes that another car in the garage matches a vehicle from a recent hit-and-run, Polly admits that the car’s owner, Robert Kendall (Chuck Couch), is hiding in her house and that he was drunk at the time of the accident. Williams’ first underscore cue begins quietly as Kendall emerges from the residence, then crescendos to a dramatic chord laced with trills as he slaps Polly and the program freeze-frames for the opening credits (which use the Harry Sukman theme).

Polly’s Tune

Williams introduces his main theme for the episode (“Polly’s Tune”) as the first act opens and the episode credits unfold over a shot of Polly reading a magazine in the waiting room of Dr. Richard Starke (Ralph Bellamy).

Polly Meets David

During her first session with Starke (a court-ordered alternative to a jail sentence), Polly reveals her history of relationships with abusive men. Williams’ music returns when Starke leaves Polly alone in order to consult with his colleague, Dr. Paul Graham (Jack Ging). Looking for a cigarette, Polly checks the waiting room, where she encounters another patient arriving early for an appointment, David Marne (Robert Loggia). Quietly ominous music underscores their initial conversation, shifting to Polly’s theme as she works her charms on David.

Starke Worries

After convincing Graham to assist in the treatment of Polly in an effort to “keep her away from men,” he returns to his office to find his patient missing. Williams’ music signals his concern, which doubles when he finds her chatting with David. A rising horn line leads to a bold brass fanfare for an act-out.

Polly Ad Libs

David begins his session with Starke by recounting his conversation with Polly, during which he failed to mention his marital status. A muted trombone crescendo marks a cut to Graham’s office, where the psychiatrist administers an inkblot test to Polly. Bass clarinet and dissonant brass drive an ominous passage as she envisions a man beating a woman but lies to Graham, saying that it appears to be an innocent mother and child. A dark ascending horn phrase covers a transition back to David’s session, with a woodwind crescendo leading to the moment when he pounds his fist into his palm.

Polly’s Theme

A solo piano rendition of Polly’s theme plays as source music on a cut to a restaurant, where Starke and Graham discuss Polly’s case.

David Visits Polly

During a session with Starke, David informs his doctor that he has begun a relationship with Polly, even though she now knows he is married. Dissonant chords introduce a flashback to the previous evening, yielding to a languid setting of Polly’s theme played first by trombone as Polly and David discuss his marriage. The cue ends with an ascending vibraphone pattern as Polly mixes David a drink.

Polly’s Rationale

Polly theorizes that David’s wife has been rejecting him, rather than the other way around (even though David has been the only one committing infidelity). A bassoon duet marks a transition out of the flashback, with an ascending brass phrase for a scene change to a subsequent session involving Polly and Starke.

Starke’s Theory

Starke asks Graham to help treat Polly. Williams’ music enters when Starke reveals his fear that Polly is suicidal and searching for a man who will facilitate that end, then builds to an act-out.

Polly’s Solitude

Starke challenges David’s assertion that he no longer needs analysis. A three-note brass phrase marks a transition to Polly’s house, where she sits alone in the dark, solo clarinet dominating as she musters the courage to call David’s house, where his wife Vivian (Bek Nelson) nearly answers the phone.

David Levels

After an argument with Vivian about the phone call, David admits that the call was not a wrong number, as he originally claimed. This brief cue crescendos dramatically for an act-out.

The Poem

Starke reads a poem that Polly wrote for him. Williams’ music simmers unsettlingly as Graham concludes that the poem is actually a suicide note, then crescendos as Starke calls Polly. A vibraphone chord marks a cut to her house, where she answers the phone.

Polly’s Blues

Polly denies any dark undercurrent to her poem, putting on a record that plays this upbeat jazz number in the background.

Polly Provokes David

Starke and Graham hatch a plan to intervene before Polly can commit suicide. Increasingly nervous woodwind phrases build to the moment when David arrives at the psychiatrists’ office and embraces Polly, then subside as David announces he left Vivian — but Polly fails to offer much of a reaction.

David Gets Upset

Low horns and high woodwinds overlap with an ominous triplet rhythm as Polly reveals she never had any intention to marry David, then crescendos as David attempts to strangle Polly.

Polly-Phonic

Solo clarinet leads to a final statement of Polly’s theme as the woman — having been diagnosed by Starke — asks Graham for help, ending with a warm major chord for the final act-out. (The witty title of the final cue plays on the musical term “polyphonic,” referring to a composition consisting of multiple lines or voices.)

Audio

In August 2010, Film Score Monthly released a 5-CD collection (TV Omnibus: Volume One (1962–1976), FSMCD Vol. 13, No. 13) that included Williams’ complete score for “The Bronze Locust,” mastered from monaural ¼″ tape.

The FSM set also included scores from M-G-M television productions by a number of other composers, along with the closing-credits version of Harry Sukman’s theme for The Eleventh Hour, as recorded on July 29, 1963, for use during the show’s second season. Several artists recorded instrumental versions of Harry Sukman’s series theme and it achieved a measure of popularity.

Video

On June 7, 2016, the Warner Archive Collection released the entire first season of The Eleventh Hour on DVD (purchase from Amazon.com); no word yet on the second season (which includes “The Bronze Locust”).

References

- “Williams and Stevens Tuning 11th Hour Segs”

Variety, 5 September 1963 - Storytellers to the Nation: A History of American Television Writing, Tom Stempel

Syracuse University Press, 1996. 307 pp.

ISBN: 978-0815603689