John Williams in Seattle

By Jeff Eldridge

September 28, 2017

When John Williams walked onto the Benaroya Hall stage last night to conduct his first-ever concert leading the Seattle Symphony, the audience erupted in a thunderous standing ovation before he even had chance to give a downbeat — a rare show of affection for a visiting conductor, but one to which the composer is no doubt accustomed, given his status as a living legend of film music.

Williams opened the program with his own arrangement of “Hooray for Hollywood” (music by Richard Whiting, lyrics by Johnny Mercer), which he recorded with the Boston Pops in 1989 and often uses to begin concerts — accompanied here by clips from classic films. (Trivia note: “Hooray for Hollywood” is the only music heard in Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye other than varied renditions of Williams’ title song, which also features lyrics by Mercer.)

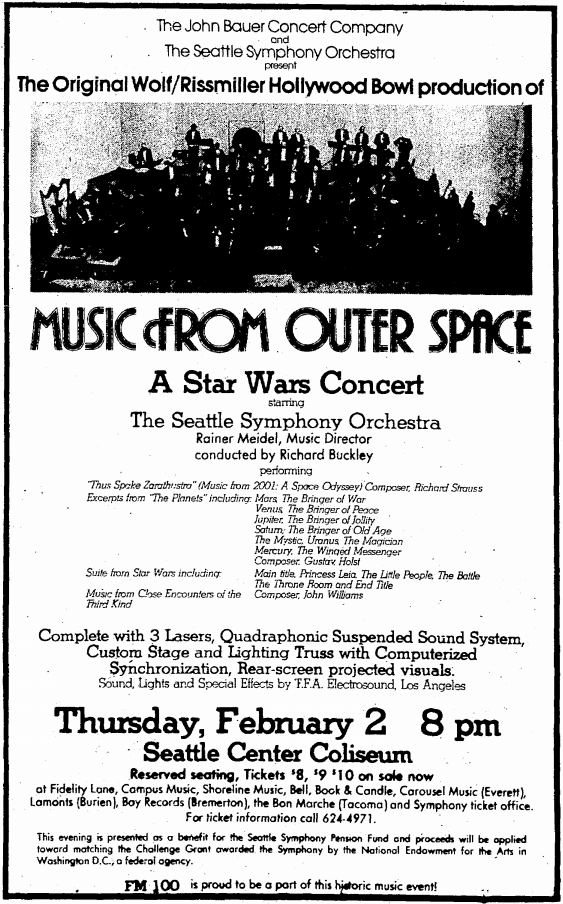

Then came excerpts from Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Williams didn’t bother turning the pages of his score, instead making eye contact with the musicians and shaping phrases in a performance that offered moments of sheer musical poetry. Turning to the audience, he expressed his delight at being able to work with this “great Seattle orchestra” whose “reputation goes far and wide” and fondly recalled that the Seattle Symphony, under its music director Milton Katims, was one of the first orchestras to play his 1965 concert work Essay for Strings. (A Seattle Times review of that January 15, 1967, performance said “Williams has had a successful career as a composer for television and the movies,” which reads as an extreme understatement some 50 years later.) The Seattle Symphony was also one of the first orchestras to perform music from Close Encounters of the Third Kind (at a February 2, 1978, Star Wars concert).

Williams continued with selections from two more Spielberg films. He described the screen action “Flight to Neverland” accompanies in Hook, noting that the “ending is slightly adjusted because it ends softly in the film,” which he replaced with something more “emphatic” for concert purposes. Next up was “A Child’s Tale,” his suite from The BFG, music that must have been new to the orchestra, but which they nevertheless played with precision; the composer gave principal flutist Demarre McGill a solo bow.

The first half of the concert closed with three selections from Star Wars films. Williams reminisced about working with Kenneth Wannberg (who was in attendance at the concert) on the 1977 original four decades ago, never imagining there would be a second film, let alone an eighth due out this December. The composer advised the audience to pay attention to the virtuosity of the Seattle Symphony’s musicians in “Scherzo for X-Wings,” saying he loved to perform the piece in concert “because you can’t do a film like Star Wars without a great orchestra.” And he recounted how he agreed to score The Last Jedi because he didn’t want anyone else composing for Daisy Ridley, with whom he had fallen in love when he first screened The Force Awakens (while noting that she is “younger than my youngest grandchild”). Audience cheers greeted the massive initial B♭-major chord of the main title from Star Wars, which led to intermission.

The second half opened with a selection not in the printed program: the theme from Jaws, which elicited giggles from the audience once the familiar shark motive emerged from the cue’s opening dissonance. “That was for my friend Steven Spielberg,” Williams explained. “Ladies and gentlemen, welcome Steven Spielberg.” At which point — to the utter surprise and immense delight of the Benaroya Hall audience — Spielberg himself walked out on stage, met by a roar that must have rivaled anything heard at the Janet Jackson concert taking place across town or the Seattle Sounders game underway at CenturyLink Field. “Oh my God,” quipped the legendary director, “I should move here after that.”

That moment when John Williams surprises you by announcing that his friend, Steven Spielberg, will narrate the rest of the concert! ?? pic.twitter.com/OQxsD5xvYJ

— Seattle Symphony (@seattlesymphony) September 28, 2017

Spielberg has tagged along with Williams to introduce music from his films several times in the past (from the Boston Pops to the New York Philharmonic to the Detroit Symphony) but these appearances are typically announced well in advance as an additional incentive to drive ticket sales. With the concert having sold out long before single tickets to the current Seattle Symphony season became available to non-subscribers, orchestra management kept the director’s appearance under wraps.

Williams sat on a stool and listened as his collaborator of 45 years (their latest joint effort, The Papers, reaches theaters in December) likened film to lightning and film music to thunder, which often lingers in the ear long after the flash of light has become a dim memory. He also mentioned that a couple of his own films feature music by “Johnny” that has become far more popular than the movies themselves. Introducing “Dartmoor, 1912” from War Horse, he asserted that “John’s music came from the richness of the soil” on the picture’s English locations. The touching performance opened and closed with cadenza-like solos by associate principal flutist Jeffrey Barker; Spielberg touched his hand to his heart at the quiet conclusion.

“Now you’re going to see why we’re on our [45th] year of working together,” Spielberg teased as he introduced a clip of the circus-train sequence from Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. “It will seem quite long without the music,” he noted. The clip played with dialogue and sound effects only, the SSO musicians craning their necks to watch along with the audience. The director drew attention to several moments where Williams would provide musical emphasis, and proudly observed that the concluding segment in the magicians’ car was “one shot.” The SSO then performed Williams’ music for the segment as the clip ran again.

Williams next led the orchestra in the balletic “The Duel” from The Adventures of Tintin, accompanying a montage of swashbuckling exploits (from Errol Flynn and Basil Rathbone to a lightsaber-wielding Yoda). Spielberg left the stage after introducing SSO assistant concertmaster Cordula Merks as soloist in the theme from Schindler’s List, afforded a touching rendition by Merks, with sensitive support from Stefan Farkas (also given a solo bow) on English horn. The director returned for the final scheduled work, “Adventures on Earth” from E.T., obviously content as he sat between the concertmaster and the conductor.

After much applause and a couple curtain calls, the composer resumed the podium. Encores at Williams’ concerts can be rather predictable, often including the theme from Superman, “Yoda’s Theme” and “The Imperial March” from The Empire Strikes Back, or the main title from Star Wars (if it hasn’t already been played). But with Steven Spielberg in the house, you play music from Spielberg films. The director introduced Williams’ uplifting “With Malice Toward None” (in the version for string orchestra) that underscored Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural address in Lincoln, which opened with an eloquent solo by associate principal cellist Meeka Quan DiLorenzo. (Surely some in the audience might have been thinking that America could use Lincoln right now — even if we had to make do with a bit of Lincoln instead.)

Spielberg then held up a single index finger as if to ask, “One more?” The response was predictable and Williams closed the evening with an energetic reading of “Raiders March,” repeatedly exchanging grins with Spielberg. Both men seemed to be enjoying themselves very much. As did the orchestra, with many musicians sporting wide smiles and the ensemble applauding their guest conductor enthusiastically. After Williams bid the audience a final goodbye, he remained just offstage, greeting the musicians warmly as they exited, many of them lining up to pose for selfies with the celebrated composer.

Throughout the evening, the orchestra was in top form, with seldom a misplaced note. Especially impressive was the brass section, led by principal trumpeter David Gordon, in a demanding (and no doubt tiring) program. Seattle waited a long time for its first visit from John Williams. It’s safe to say those in attendance Wednesday night can hardly wait for his second.